IAPI – the Institute of Analytical Plant Illustration

How the days fly past – this time last week I was on my way to Birmingham to speak to IAPI – the Institute for Analytical Plant Illustration. Not my usual way of spending a Saturday, but it was worth the travel. The invitation to speak came through botanical artist and IAPI member Valerie Oxley when we finally met in person last January at the botanical art symposium held at the Linnean Society. Before that, back in 2007, we had been contact about including one of my digital composite plates in her book ‘Botanical Illustration’ , but only by email.

I arrived to find very a welcoming group and an interesting mix of not only painters and botanists, but also photographers. The group has a number of well known botanical artist and illustrators and botanists, so I had been a little apprehensive beforehand, but I was delighted in their degree of interest in my digital images, and we had a lively discussion after my presentation.

I came away with several copies of their journal Eryngium, which, I had noted in advance, contained articles I wanted to read. It is published annually (in January) and contains interesting articles relevant to scientific botanical illustration – lots of ‘how to’ articles, notes on specific botanical features as well as more general and historical botanical illustration topics. Take a look here if you want to see the contents of the back issues of Eryngium.

I discovered they have members from all over the country – remarkably I had not come the furthest by any means. So, thank you IAPI for your welcome and friendship, not to mention the lunch. I have just sent off my membership application form and look forward to being part of the group.

2016 – A new year for digital botanical illustration

First of all, a very Happy New Year to anyone reading this blog!

Last year turned out to be a busy one for me, and my botanical illustrating posts had to take a bit of a back seat. But my resolution this year is to get back to this blog and to continue my explanations about my composite botanical illustrations.

However, next up for me is a trip up to Birmingham, to the Winterbourne Botanical Centre where I have been invited to speak at the Institute of Analytical Plant Illustrator’s AGM. I’m looking forward to meeting the IAPI members and learning more about their society – and so will post soon about my visit.

5. Freedom of movement – flexibility in digital botanical illustration

From talking to others it seems that my images are often thought to be collages, but that is not how I see them, or indeed work with them. And since this relates to my previous post about overlap, it seems a good time to clarify this misunderstanding.

I want to emphasize that my images are not collages, at least not in the traditional sense of being irretrievably pasted down to form a fixed final image. These images are free, only becoming permanently fixed at the point of printing on to a medium such as paper or board. Onscreen, the elements need not be fixed to any background, nor to each other. All the component parts within a composite arrangement exist and function as separate ‘floating’ entities which are independently moveable, sizeable and interchangeable. The parts may be fixed into a position for a particular purpose, but not irretrievably, and there is the option for many different final images. This distinction is important as it has so many implications, only one of which is the advantage of being able to bring partly obscured parts forward to make them visible. Most importantly it means that while the images may be created for one purpose, that they can be readily altered and used again and again for a wide variety of different purposes. Numerous benefits other than the ability to reverse any overlap, notably include the flexibility of composition and the potential for interactivity.

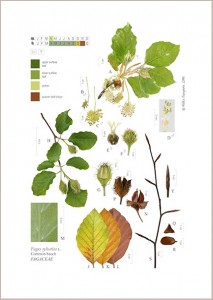

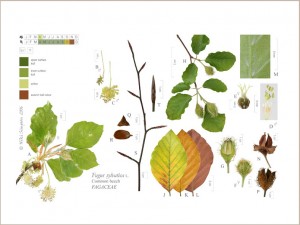

Primary image

Secondary image

To give you just one example of what flexibility of composition allows, a vertical composition can be very easily and quickly modified to suit a horizontal format. For example, here is my illustration of the common beech, Fagus sylvatica. Above is my standard layout or portrait version, while below the same image has been re-composed to one of many possible secondary arrangements, in this case a landscape format. To achieve the new (well hardly new; it was created for inclusion in my Digital Diversity brochure in 2007; see pp.6-7 if you have a copy) horizontal composition, all the ready-scaled parts have simply been re-arranged. I consider the portrait versions to be my primary or core images.

And why you may ask, might it be an advantage to have an image that can be orientated either way? Well, by having the potential for both options (and indeed others), anyone commissioning an illustration gets the option to speedily get a secondary arrangement at a later date, since all that is needed is to re-arrange the same ready-scaled parts. There may be all sorts of reasons for differing formats, but notably, a horizontal composition has relevance for display on computer monitors, while the potential to be adjusted for whatever aspect ratio format is required, has relevance for the evolving dimensions of mobile phone and tablet screens.

So these illustrations, have an inbuilt resilience to changing requirements through their flexibility and adaptability. Whether digital photography or digital drawing, the freedom the digital medium allows is breathtaking – the images created really are re-layerable, re-arrangeable, re-composable, re-sizable, re-scalable, re-orientatable, correctable, updatable, etc., meaning that the images should be seen as truly flexible multi-purpose images, and ones with a future that we probably cannot fully comprehend at the present.

4. Hidden but not lost – overlap in botanical compositions

This post is about how I use ‘overlap’ in my own illustrations and how it is one of the advantages of working with this digital technique. And by overlap I mean the overlapping of plant parts when compiling a composite botanical composition. So to be clear, that though related, this is quite distinct from the Stage 3 of the same name, in Anne-Marie Evan’s widely-known botanical painting technique, where ‘overlap’ refers to the shadowing required for painting overlapping pieces within a single part in order to show clearly which pieces of it are in the foreground, middle distance or background.

Botanical artists among you reading this blog, and those used to looking at historical botanical illustrations, will know of course, that the overlapping of component parts within a composite illustration is nothing new. It is a long-standing convention, that has been employed by many botanical artists, and which developed simply as a way of fitting large parts at life-size into a limited page space. So it was generally used for illustrating large plants, often large leaves, so that a leaf (or even part of a leaf) was shown behind the other part/s. In more contemporary work, overlap has been used to create unusual and often striking contemporary compositions – the wonderful paintings by Pandora Sellars spring to mind.

A look at the illustrations in my galleries will show you that in the composition of my botanical illustrations I often show overlapping plant parts, typically the leaf upper and lower surfaces (generally with the upper leaf surface shown in front of the lower one). However, as shown above, I have also used it to show the characteristic transition of leaf colour from later summer green through to autumn colour, prior to leaf fall for deciduous trees. While such colourings are generally characteristic of the taxon, it is not diagnostic. As such there is no botanical requirement to show the entire leaf of each one, as I show the leaf shape, margin and venation in other parts.

This is quite a fun bit of working digitally – as each plant part can be placed in its entirety on its own virtual layer, and so is simply a layer within an arrangement of layers. In the left hand example above, of autumnal liquidambar leaves, the green summer leaf has been placed on the top layer and is the one viewed as in front. The 5 leaves further back are shown as partly obscured by this one in front, but it is a trivial matter to alter the sequence of layers and so reverse the overlap and so bring any of the partially hidden ones to the front. Unlike a painted or drawn version then, where the parts are fixed, the obscured parts may be hidden, but they are not lost, and can always be ‘retrieved’ if needed – either to alter the composition or for botanical study.

In the right hand example I have reversed the leaf sequence to now show the darkest brown leaf as the one whole leaf at the front. But of course being digital, I can show whichever leaf of the five I choose to be in the front …or even change my mind at a later date!

Change – botanical illustration in an age of change

I came across this quote the other day:

“All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second,

it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.”

Arthur Schopenhauer, German Philosopher (1788-1860)

I don’t know about “all truth”, but happily my digital work has gained support over the years and appears no longer to be laughable. Over the years I have increasingly received lovely, appreciative emails from around the world, from botanists, horticulturists, gardeners, nature lovers, teachers, architects and designers of all sorts, but also notably from some open-minded botanical artists, such as the very talented botanical painter Coral Guest. (Take a look a Coral’s website to get an idea of the quality and scale of her work, but do also make a point of visiting her separate and interesting blog, in which she writes very perceptively about Botanical Art and which I highly recommend.)

I am also delighted to acknowledge the support of the Royal Horticultural Society, by purchase of images and by exhibitions of my illustrations at the RHS Lindley Library, Wisley and RHS Hyde Hall. My digital botanical images have been on show in The Garden Museum and the Linnean Society in London, as well as at the BGBM in Berlin, at the invitation of Herr Professor Walter Lack (botanical art expert and author of Garden Eden). At least two (that I know of) digitally-created botanical illustrations have now been displayed in the dedicated botanical art gallery, the Shirley Sherwood Gallery at RBG Kew – one of mine in their Power of Plants exhibition in 2009 and one by Laurence Hill in their Inspiring Kew exhibition last year.

However, some opposition to my digital images remains, though thankfully it is now more in the sense of avoidance or quiet resignation, rather than of the previous outraged opposition. But, regardless of the fact that groups who provide opportunities for botanical artists and illustrators to exhibit (such as the SBA, BISCOT, ASBA and the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation) still choose to exclude this type of work in their exhibitions, I feel it is self-evident that my images are botanical illustration, no more and no less.

3. Mixed media in the botanical illustrations

Since many of my illustrations are composite images, they lend themselves to mixed media work, where parts created in different media can be combined together within the final image. But not mixed media in the traditional botanical artists’ sense of, for example, pen and watercolour, but digital mixed media. By this I mean any combination of digital media, such as flatbed scans, digital photographs, scanned conventional printed photographs and digitised slides (both black and white or colour), scanning electron micrographs, digital sketches, digital line drawings, digital diagrams, as well as scanned hand drawn artwork.

As my earliest illustrations were all created from photographs taken before I had a digital camera, most of the parts within those illustrations, (such as the mistletoe) were created from photographic slides scanned on a home scanner. Also in the early days, as a beginner photographer, I was sometimes unable to get a satisfactory photograph of a part and so I tried out using a digitally drawn diagrammatic parts instead. This worked fine, but turned out to be temporary measures, since I was able to replace them the following year with a photographic parts, which clearly showed far more.

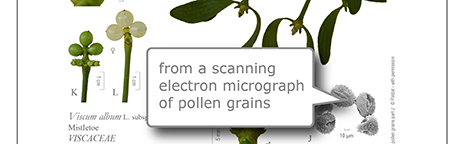

Central portion of my composite illustration of mistletoe,

compiled using mixed media

© Niki Simpson 2015

To see examples of what I mean by digital mixed media, take a look at my illustration of mistletoe, Viscum album above, where I have used a black and white line sketch drawing to show the habit (part A). For another example, see my illustration of the cuckoo pint, Arum maculatum, in my gallery, in which the habit (part R) is also shown as a line sketch, this time in sepia, not black.

Lower portion of my composite illustration of mistletoe,

including a SEM of pollen

© Niki Simpson 2015

Pollen grains part J: © PALDAT – with written permission

A different example of mixed media within an illustration, can also be seen in the mistletoe illustration, where I included a scanning electron micrograph to depict the pollen grains (part J). These micrographs are by default black and white, but while lacking colour information, still provide additional descriptive information of the taxon. Please note that I did not take this SEM myself – I was kindly given permission from PalDat in 2007 to use one of their images and to isolate the pollen grains from the original background, in order to be able to trial the use of a pollen SEM within this type of digital composite botanical illustration. The resulting composite image was included in my exhibition entitled Digital Diversity at the BGBM in Berlin that year.

Flatbed scans can be good for flat, very 2-dimensional plant parts, such as leaves, but I now rarely use these, as I find it is difficult to get the lighting to look consistent with the other photographed parts within the final illustration, where I am better able to control the direction of the lighting and to minimise the shadows the plant throws, both on itself and on to the background.

But, while my composite images can be mixed media, you will see in looking through the illustrations in the galleries, that for most illustrations I have only used photographic parts. This is because my first choice is nearly always for a photographic part (that is where I am able to achieve a photo which shows the information I want it to) – and this is for important reasons. A photographic part is, when simply isolated from its background and not manipulated, surely as close to the ‘botanical truth’ as one is going to get in a 2D representation – full realism, yes, but importantly, further realism and detail as well, since hidden descriptive details can be revealed on enlargement, literally at the touch of a button. (See my previous post below Part 2. Enlarging hidden details). Unlike photographic parts, a line drawing, whether digital or hand drawn, on the other hand reveals nothing further on enlargement. The ability to considerably enlarge my images to reveal further features is an aspect not apparent to those simply seeing this type of image either as paper prints or as small, low res images on a webpage.

2. Enlarging hidden detail

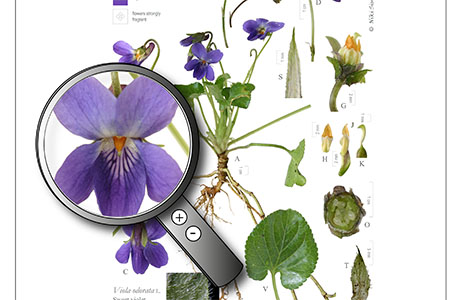

Portion of Viola odorata illustration

with a virtual magnifying glass

© Niki Simpson

One of the benefits, indeed one of the fascinations and delights, of working digitally with photography for illustration work is the ability to zoom in, literally at the touch of a button, to reveal otherwise hidden detail. Photography enables the capture of considerable amounts of descriptive data – fine details of hairs, pores and other micro features, that may or may not be diagnostic – in an instant, and which can be readily revealed by enlargement. Of course this is nothing new – it was appreciated back even in the days of the earliest photographs.

“One advantage of the discovery of the Photographic Art will be that it will enable us to introduce into our pictures a multitude of minute details which add to the truth and reality of the representation“- Fox Talbot, 1844

Indeed a number of botanical artists have used this aspect of photography to help create their highly detailed botanical paintings of close-up views of plants. Botanists too are well aware that photographic detail is much clearer on enlargement and have been enlarging photographs for many years as part of studying their plant subjects.

But with the advent of digital technology, this access to otherwise hidden detail is made so easy. I created the image above with a virtual magnifying glass to hint at the hidden depths to these illustrations and also how this sort of image could be used to engage a younger audience for educational purposes. But if you look at one of these images on a smart phone or tablet, it is already possible to see this detail without a virtual magnifying glass – a simple pinch and reverse pinch with your fingers will reduce and enlarge such images, and then you can pan around the illustration to explore the detail. On one level, as a botanist or keen plantsperson, you can observe and study the diagnostic features of interest to you, while at another you can just simply have fun moving around the illustration as the fancy takes you, exploring to see what you can find, what parts look like enlarged and perhaps see parts you have never seen before.

Enlarging an illustration on an iPhone

© Niki Simpson

On a desktop or laptop, illustrations can readily be enlarged simply using the +/- zoom tools and the viewer can similarly pan around the illustration at any chosen magnification. However, with today’s sophisticated zoom tools and with interactive programming, the scaling and magnification of the contents of an illustration need not be limited to this – a viewer can pick up a virtual magnifying glass to view just a portion of an illustration enlarged. Even in 2007, the virtual book I created for my exhibition at the Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum, was created using Touch & Turn software that used a magnifying glass which cleverly scaled just the portion under the lens incrementally up or down as the viewer moved it across the page, and all at the same time as the illustration was on a virtual page which could be turned by clicking and dragging a mouse.

Pages from my page-turning virtual book Digital Diversity

on show in 2007 at my exhibition at the BGBM, Berlin

© Niki Simpson

I am sure botanists already regularly enlarge photos of their plant subjects to study onscreen in the line of their work, but, as yet, do not expect it from within an illustration.

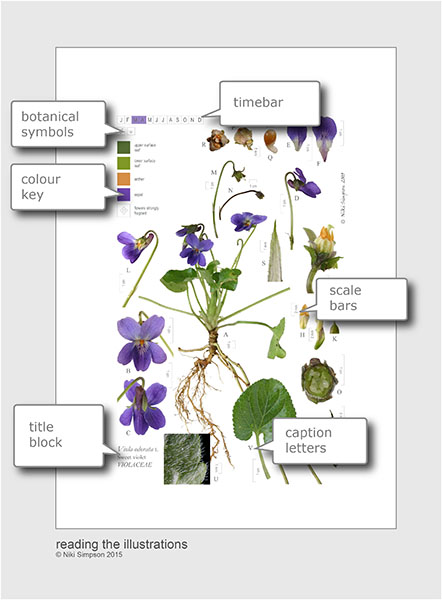

1. Reading the botanical illustrations

Part of the reason for setting up this new website, is to find ways to demonstrate and help explain my images. So I have been experimenting with ways to do this and this is the first post along these lines. I plan to considerably expand the About page, but in the meantime, this is a quick summary of the main parts to these illustrations. I hope to go into each of these more fully later.

Features like the title block, scale bars and the lettered parts are long standing conventions used in published botanical illustrations and will not be new to botanists and those used to looking at botanical illustrations, but the colour key, timebar and botanical symbol set are new features which I developed and designed during 2005 – 2006, specifically for inclusion in my digital images.

Title block

The title block, usually in the bottom left hand corner, contains the currently accepted Latin plant name, with the author for that name, together with the main past botanical names, or synonyms. I have also included the most well known common or vernacular names, and lastly the botanical family in which the plant is placed.

Colour key

The colour key, in the top left corner, shows standard colour references for notably coloured plant parts. For this I have used the RHS Colour Chart which has been specially developed for recording plant colour.

Timebar

The timebar, again in the top left, shows a lettered block for each month of the year; those coloured indicate the month/s of flowering. In the violet example shown, it can be seen that the species generally flowers March – April.

Botanical symbols

Botanical symbols are used within each image to convey the sexual arrangement, life form and various other features of the plant, such as smell and toxicity, that are otherwise difficult to depict. For example, in the violet illustration shown above, the botanical symbols indicate that the plant depicted is a non-woody perennial, is hermaphrodite and has scented flowers.

For the key to the full botanical symbol set, go to Symbols.

Scale bars

All parts and dissections are shown to scale by a metric scale bar. Traditionally measurement information was often included by using a multiplication sign for the number of times the part was enlarged, for example ‘x3’. However, for digital images, viewed onscreen, using scale bars means that, at whatever size the image is viewed onscreen, the scale bars are accurately rescaled automatically.

Caption letters

Each composite illustration aims to be a scientific reference-standard plant portrait of a single taxon or plant species, showing the diagnostic, and where space allows the characteristic, features of that plant and so the plant parts are lettered to refer to a full caption for the illustration. This is my default layout, but of course, being digital, it is just a simple matter of hitting the ‘Delete’ button to remove the letters if they are not required. Using the violet illustration shown above as an example, the caption would read like this:

A: flowering plant showing stolons, normal flowers only; B: flower, front view; C: flower, back view showing detail of calyx; D: flower stem with paired bracteoles, side view of flower; E: upper petal; F: central lower petal, G: flower detail, petals cut away showing androecium and gynoecium, etc.

Starting with botanical drawing and painting

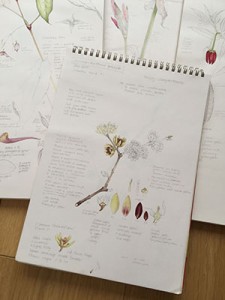

Sketch pads: pencil and watercolour study of Chimonanthus praecox

© Niki Simpson

I came to these digital botanical illustrations through painting and drawing plants. For as long as I can remember I have drawn, painted and loved plants, and I can even remember dissecting my first flower at a very young age – a cowslip, which I pressed and glued in to my school exercise book next to my painting and drawings. This interest grew, and in my teens I was given six, now treasured, parts of Stella Ross Craig’s Drawing of British Plants. I have enjoyed plants and drawing them ever since.

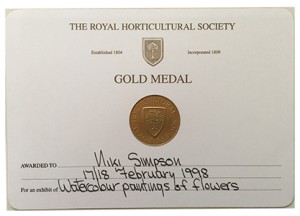

But it was many years later, at one of Anne-Marie Evans’ weekend botanical watercolour courses at West Dean College, near Chichester, that I painted a flowering branch of Magnolia grandiflora (which I still have framed on the wall) and my interest in botanical watercolour painting was re-awoken. I painted for many years, exhibiting in the RHS London Botanical Art Shows a number of times, and in 1998 was awarded the RHS Gold Medal for my exhibit of watercolour paintings. I was a botanical art tutor giving short courses at RHS Rosemoor for many years.

This botanical plate was published in The New Plantsman (1996) 3 (4): 209 in the article “Liriodendron tulipifera: the tulip-tree” by S.A. Sponberg & A.C. Bell

I had joined the RHS at Wisley first in the Plant Records office in 1993, later becoming their Horticultural Database Administrator, and so by this time, was working in the Botany Department at Wisley, which increased my interest in ‘investigative’ botanical illustration, especially in microscope work producing dissection illustrations to scale. I was privileged to have access to both the staff and the public sections of the RHS Lindley Library, Wisley and so spent hours and hours looking at an amazing array of botanical books – wonderfully illustrated in a variety of media, from woodcuts and engravings to lithographs, nature prints and photographs. The RHS Lindley Library specialises in botanical art and garden history and was given Designated status by the Museums and Libraries Association in 2011 as a collection of international importance.

By studying the content of such illustrations, both colour and black and white, I gradually developed my own botanical pencil and watercolour studies of plants. And it was as I was working in the RHS Botany Department using computers for spreadsheets and word processing, that picking up a paintbrush to paint in watercolour began to seem incongruous. I felt that the possibilities of digital plant illustration for scientific work needed to be explored if botanical illustration was going to support botanical science in the future. And so, my digitally created composite botanical images are very much based on my watercolour paintings and my botanical pencil and watercolour studies.

RHS Gold Medal for botanical watercolour paintings, London 1998

© Niki Simpson

Beginning my digital journey: Apr 2003 – Feb 2004

First exhibit in the Reception area at RHS Wisley, Jan 2004

© Niki Simpson

Many people have asked me when and how I started working digitally, so for the record, my departure from the traditional botanical art path began in April 2003, following my Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust award.

It started with a morning of beginner’s photography tuition with the lovely Anna Saverimuttu, (Anna is a wonderful portrait photographer – take a look at her work) though at that point I was unaware of the divergence that lay ahead of me. My only aim at that time was to learn how to take better photos to use for reference purposes, as back-up against ephemeral plant parts wilting. A wild foxglove and an iris cultivar were my very first models; the iris simply because it was flowering outside my front door at the time, and the foxglove, well, with the generic name Digitalis, it simply had to be one to try for a digital project – and by happy accident, it too just happened to be coming into flower at the time.

By the summer, I had plucked up courage to buy a pc and had then bravely booked four sessions of one-to-one image software training, and thought I was all set to learn to draw and paint with a digital stylus on a digital drawing tablet. I didn’t have a digital camera, had never heard of Photoshop, and Adobe products had yet to become the industry standard.

I remember the mixture of excitement and anxiety of venturing into London and turning up for my first session of software training, but then being so dispirited after it, that I nearly gave up there and then. Even after weeks of practice, my early digital attempts looked dismally either plastic or pixelated – a far cry from the realism I had hoped for. But on the third of the training days I happened to take with me a CD of a few of my iris and foxglove photos, which someone had kindly offered to test scan for me, and so saw my own photos onscreen for the very first time. I was introduced to Photoshop, saw how my photos could be scaled, literally at the touch of a button, and was shown ways to cut out a part from its background. And it was at that moment the penny dropped. There, in front of me, was a ready-digitised, accurate plant part, which I could place against a white background, capable of conveying considerable detail on enlargement, and in full realism; indeed more realistic than anything I could see I was ever going to be able to achieve by observing and digitally recreating, however much time I had. Unexpectedly then, I found myself on new botanical image territory, and that I was on my own – there were no examples to look at, books to read or precedents to follow. I had to work out what questions to ask, to experiment again and again until, after my last session at the beginning of December, I finally managed to put together my first ever digitally-created, scaled, composite botanical image – my ‘digital Digitalis’. It wasn’t perfect, but it was 2003 and it was exciting – it felt like a milestone.

Later I experimented with ways to depict leaves involving digital line drawings, flatbed scans and, after going out to buy a home slide scanner, digitised slide photographs, and then manipulating and combining them in all manner of ways, though of course some were more successful than others. These were followed by attempts to depict the ginkgo, and lastly, with the help of Bernard Boardman to dig it up, the strange but beautiful purple toothwort, as the Wisley Curator, Jim Gardiner, had kindly given me permission to use some plant material from Wisley Garden for experimental illustration purposes. Inevitably there was much trial and error, but I must thank all my RHS botany colleagues, especially Peter Barnes and Richard Sanford, for their encouragement and help throughout that first year – it was much needed.

My first digital composite illustrations then, were created during the period when I was working part-time in the Botany Department at RHS Wisley and, as a way to mark the completion of my QEST project, I had the idea to put up a small informal display of my results in the Reception area in the Laboratory building. The Director, David Gray, kindly gave his permission and so the first display of my digitally-created botanical images was at RHS Wisley in January 2004. I must thank Patty Boardman, our departmental secretary, who kindly thought to put out a notice to invite Garden visitors to come in to Reception to take a look and even put together a makeshift Visitors’ Book for me – the first public comments about my digital botanical images.